Albany

If anyone could sell you a $2 million school bus, it’s Karina Butler.

The 17-year-old spent last fall learning about hydrogen fuel cells — New York school districts must stop buying conventional diesel buses by 2027, and by 2035, Butler explained, all school buses in the state must operate electrically.

The new buses are clean, she said, but at $2 million apiece they’re also “very pricey.” That’s a tough sell for cash-strapped districts in the state’s capital region. So working with a local electrical equipment manufacturer, she and three classmates developed a pitch for the company to deliver to nearby districts.

A senior at Tech Valley High School in Albany, N.Y., Butler is by now used to this. She said she owes her confidence to the school, which pushes students to embrace discomfort and grow into their own through an unusual mixture of corporate-inspired teamwork, self-discovery and personal attention from adults.

When it opened in 2007, Tech Valley was at the forefront of project-based STEM learning. One of the early New Tech Network schools, it was conceived during a high-tech building boom, taking its name from a marketing campaign in the late 1990s to promote eastern New York State as a high-tech competitor to Silicon Valley.

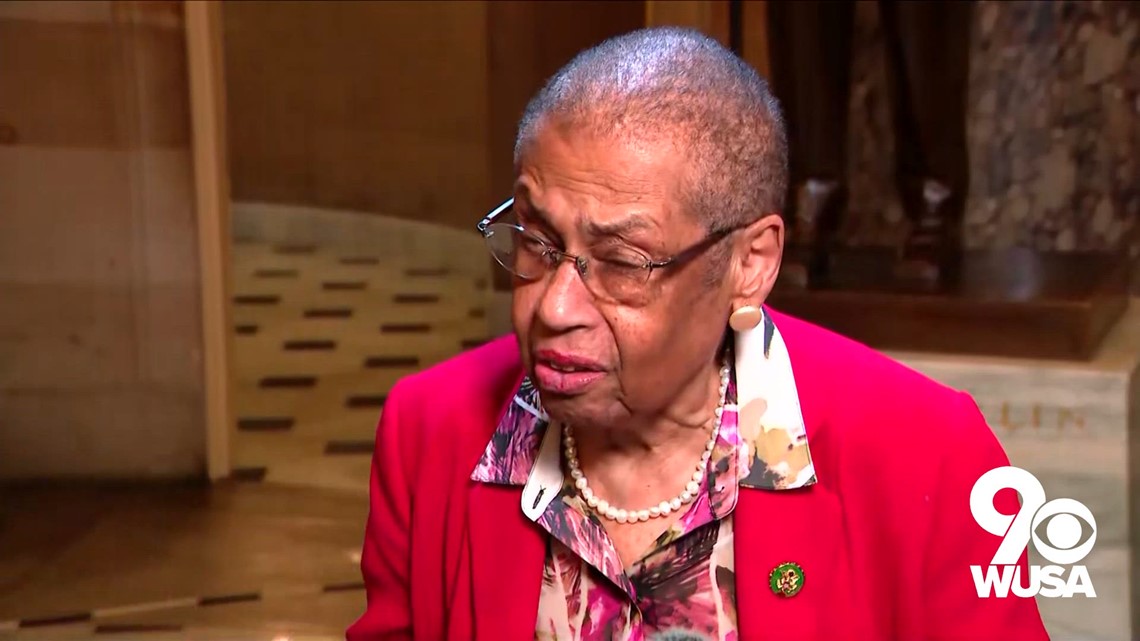

Karina Butler (right) talks with Parker Fields, a design engineer at Plug Power, a local equipment manufacturer, after she and classmates made a presentation about hydrogen fuel cell school buses. (Greg Toppo)

But while other schools built on the principles of STEM, projects or corporate partnerships have come and gone, Tech Valley has endured for nearly two decades. Now in its own boxy two-story building on another tech campus, it endures due to an unusual funding structure, small size and a close-knit community.

It’s not a charter school and it’s not a traditional district school. Technically, it’s a state-funded technical school underwritten by two regional chapters of New York’s Board of Cooperative Education Services, or BOCES, which typically offer training programs in welding, cosmetology and the like. Many rural districts rely on BOCES programs for one-off courses they can’t afford.

Tech Valley offers a BOCES program in STEM-focused, project-based learning that spans four years. Instead of a license or certificate, students earn a full diploma, taking a full load of courses that includes one year of computer science and two of Mandarin.

“I sometimes personally call it ‘a unicorn school’ because it’s something that doesn’t exist in nature,” said Sarah Hugger, Tech Valley’s outreach coordinator.

Even after 17 years, it enrolls just 150 students. As a BOCES program, the school draws students from 30 school districts via random lottery. The small size means virtually everyone knows each other.

Teacher Jennifer Muirhead (left) photographs the senior class at Tech Valley High School. Its small size attracts students who want a hands-on, personalized experience in high school. (Greg Toppo)

“You literally can’t avoid anybody here,” said junior Willow Kabel. While she’s not good friends with all of her classmates, “I’d say I’m friendly with everyone.”

She added: “A lot of us are introverts, so we don’t want to socialize. But the introverts find each other.”

In their applications, most prospective students say they’re looking for something different from what they got in their first eight years of schooling. Many write of bullying in elementary and middle school, often over gender identity. Others, from small towns, simply don’t want to continue with the same handful of kids they’ve always known.

“Everyone is coming from other districts, so no matter how many friends you had at your home district, coming here is basically starting over,” said junior George Hartman. “And I think what that really does is it puts everyone on such a level ground.”

Once they arrive, students encounter a program in which many classes are team-taught and interdisciplinary, with an emphasis on — perhaps even an obsession with — collaboration. Open-access, flexible work spaces dot the building, inviting impromptu brainstorms and conversations. Teachers long ago ditched the traditional coffee-and-donuts teachers’ lounge for a central common work space with a long work table. Students are welcome.

Long, multi-period, interdisciplinary classes are the norm rather than the exception, and teachers’ time planning lessons together “is non negotiable,” said special education teacher Danielle Hemmid.

Philadelphia’s Building 21 Pushes Students to Tackle ‘Unfinished Learning’

The school assesses students not just on communication and literacy but on their ability to work together to get things done. “We know that being able to collaborate with others is going to help you now and in the future,” said Principal Amy Hawrylchak. “So we want to give you those tools and skills while you’re here.”

We know that being able to collaborate with others is going to help you now and in the future. We want to give you those tools and skills while you're here.

Amy Hawrylchak, principal

For students, the responsibilities they bear for group projects are well understood. Unlike in many high schools that dabble in projects — these days that’s basically every school — students at Tech Valley are graded not just on their work but on how they share and delegate tasks.

Freshman Ari Story recalled that when he was assigned a project at his previous school, “I would just sit there and think, ‘What am I going to do? How do I start this? How do I continue? How do I spread it out?’ I wouldn’t know what to do”

Teachers look closely at who’s doing what and assign (or withhold) “collaboration points.” Senior Teddy DuBois noted that in a few circumstances, teachers might even check the revision history on a shared document to determine if one person typed it all. Typically, though, teachers get good at spotting team members who are skating by and letting others do the work.

Eventually, skating by catches up: After three warnings, a student who’s not participating can be removed from a team and lose valuable points.

“Here, if you don’t work together, you don’t really pass, and you don’t do well,” said Hartman.

Hawrylchak studied student and teacher agency in graduate school and as a result the school is thick with it. Virtually all clubs and activities, from debate to drama to flag football, are student-run.

To Combat Nursing Shortage, Rhode Island Charter Turns to High School Students

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the school attracts a large number of neurodivergent students. At last count, 35% of Tech Valley students arrived with either an individualized education plan or a less restrictive 504. Even with such a small student body, the school employs three full-time special education teachers.

“We’re bridging this gap between who you were in elementary and middle school and how you are going to function in college,” said Hemmid, the special education teacher. That most commonly looks like helping kids develop so-called “executive functioning” skills that allow them to work independently.

The goal, she said, is to help every graduate do well in college with minimal accommodations such as more time on exams or extra help in a writing center.

By planning together, Hemmid said, teachers are able to anticipate the challenges students bring and navigate them. “The classroom just runs and it should be so that I don’t need to say, ‘Quick, let me prepare something so that my students can do this work.’”

While a direct comparison with local high schools is difficult, Hawrylchak said that with few exceptions students attend Tech Valley all four years. Of those, virtually 100% graduate.

“Students who stay here graduate,” she said, “and have since we started.”

I-Term and ‘ikigai’

Once a year in the winter, all classes stop for a week so students can take part in a schoolwide “I-Term” that matches them with community partners to explore careers. Like much of the curriculum, the project is guided by the Japanese principle of “ikigai,” or purpose. It asks students to consider not only what they love to do and are good at, but what the world needs and what they might someday do well enough to earn a living.

A chart displaying the four principles of ikigai. (Greg Toppo)

As freshmen, students explore openly, Hawrylchak said — many freshman boys take this opportunity to shadow game designers at local studios, for instance. But by sophomore year, teachers are asking them to think more holistically about their purpose. “We’re saying, ‘O.K., now we want to add the layer of: What are you good at?’”

It gets more complex: As juniors, they must confront not only their tastes and abilities, but whether the world needs what they have to offer — and how they can make a living doing it.

Pretty soon, Hawrylchak said, “They’re aware of this entire Venn diagram” that encompasses a larger sense of purpose. That’s when they begin job-shadowing for a week as juniors. As seniors, that becomes a two-week commitment, offering “a deeper, richer experience,” she said.

High School 2.0: These Teens Build Drones, Research Cancer & Try Out Careers

It all leads to a lot of soul-searching, with students often taking years to narrow down their ideas. One student who loved soccer spent her first I-Term shadowing soccer coaches at both the high school and college levels, then developed an interest in politics and worked in a state senator’s office and, later, for a legislative lobbyist. She eventually attended the U.S. Coast Guard Academy, intending to study politics.

“My deepest hope is that the kid exits high school with a sense of maybe, ‘These are some things I don’t want to do,’ ” Hugger said. “ ‘These are not things that inspire me or make my heart beat fast. And maybe here’s the thing that I do want to do.’ ”

‘The more times I do it, the more skills I learn’

Each fall, seniors spend about six weeks on a capstone project in which they partner with a local business — given the region, that can mean anything from a small advertising studio to IBM or State Street Bank.

Students take a day to “speed date” with company representatives and figure out which one they want to work with. Then they settle in and work out solutions to a problem the company presents.

For one group this winter, the challenge was to design soundproofing surfaces for a makerspace in nearby Troy. DuBois, who wants to study engineering, designed a chandelier that absorbs sounds and a gaming surface that turns into a moveable, soundproof wall, while a classmate proposed panels filled with homegrown mushrooms that absorb sound.

Seniors Teddy DuBois and Lee Suto present their designs for soundproofing for a local makerspace during a capstone showcase. (Greg Toppo)

Butler recalled that she was an abysmal public speaker when she arrived at Tech Valley as a freshman. She would cry, laugh — or both — when called upon to make a presentation. Four years later, she is now quite comfortable in front of a crowd. “The more times I do it, the more skills I learn. You get better at it.”

I wanted to go (here) because they said that you get to go out on your own, discover who you want to be.

Karina Butler, student

After graduation this spring, she’s hoping to study education or museum curation at a nearby state university campus — she has always loved wandering through museums, ever since she visited one that her grandmother cleaned.

Her previous school couldn’t come close to what Tech Valley offered: 100 community service hours, working with business partners, job shadowing.

“I wanted to go [here] because they said that you get to go out on your own, discover who you want to be, what you are going to be,” she said. “Instead of just sitting in traditional classes and people talking to you about their careers, you got to experience that.”

.png)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·